Alex Kudera’s award-winning novel, Fight for Your Long Day (Atticus Books), was drafted in a walk-in closet during a summer in Seoul, South Korea. Auggie’s Revenge (Beating Windward Press) is his second novel. His numerous short stories include “Frade Killed Ellen” (Dutch Kills Press), “Bombing from Above” (Heavy Feather Review), and “A Thanksgiving” (Eclectica Magazine).

Thursday, July 31, 2025

Sunday, July 27, 2025

Saturday, July 26, 2025

Friday, July 25, 2025

Monday, July 21, 2025

two for one

I'm excited to announce that this fall, Rick Harsch's Corona\Samizdat Press will publish as one volume the corrected version of Fight for Your Long Day and the sequel to my debut novel. What further adventures await Cyrus Duffleman? Is our adjunct hero even alive?

Saturday, July 19, 2025

Friday, July 18, 2025

Thursday, July 17, 2025

Wednesday, July 16, 2025

Saturday, July 12, 2025

John Martin, rest in peace

Thursday, July 10, 2025

it didn't kill brain cells

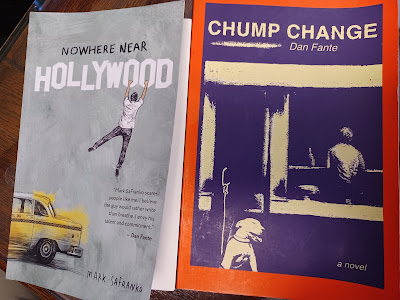

"Now I had customers up the [caboose]. Bosses, too. Welcome to Hustle-for-a-buck, USA. In the near term, the [redacted] at the six-top was screaming for refills like he intended to spray his hose all over his mother-in-law after Friday brunch. He pulled a "Sir, please" the first two times, and then shifted to no voice or eye contact with a triple spoon clink against his water glass after that. Fucking annoying, yeah, but all I had to do was hustle to the table and refill the cup. It was work. Straightforward. My first job of the day, and it didn't kill brain cells I needed for my next gig."

Wednesday, July 9, 2025

Tuesday, July 8, 2025

Monday, July 7, 2025

Friday, July 4, 2025

Thursday, July 3, 2025

Featured Post

Short Stories by Alex Kudera

"A Separate Piece," Citywide Lunch , December 8-12 , 2025 "A Day's Worth," Eclectica Magazine , July 2025 "C...

-

Iain Levison's Dog Eats Dog was published in October, 2008 by Bitter Lemon Press and his even newer novel How to Rob an Armored Car ...

-

Book Reviews: "The Teaching Life as a House of Troubles," by Don Riggs, American, British and Canadian Studies , June 1, 2017 ...

-

In theory, a book isn't alive unless it's snuggled comfortably in the reading bin in the bathroom at Oprah's or any sitting Pres...

-

Beating Windward Press to Publish Alex Kudera’s Tragicomic Novel Illustrating Precarious Times for College Adjuncts and Contract-Wage Ame...

-

W.D. Clarke's Blog " Fight for Your Long Day, by Alex Kudera " by W.D. Clarke (January 13, 2025) Genealogies of Modernity ...